In the early 1950s, the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan helped to establish a Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) pilot training program to meet the emerging Cold War requirements. In the wake of World War II, there was a desperate need for military pilot training – whether it was for NATO squadrons in the defence of Europe, NORAD forces in defence of North America or with the UN units employed in worldwide peacekeeping operations. Robert Heckadon joined the University Reserve Training Plan (URTP) in 1952 as a summer job, but the experience ended up shaping his entire future.

He began his training in RCAF station. Centralia and learned how to fly the Harvard Basic Trainer, the T33 Jet Trainer and the Mustang. All of Robert’s instructors were veteran WWII fighter pilots.

“They were excellent pilots,” Robert wrote in one of many emails to his kids, detailing his flying experiences. “As a student you didn’t dare ask these guys for stories, but these guys knew much more about flying than what the Air Force had, as they could teach from real life experience.”

Once when flying at 20,000 feet and one of the instructors suddenly appeared above his plane, upside down in another T-33 about 15-25ft above, waving down at him – just like in the movie Top Gun.

In another story, he recalled “flying with an instructor for about an hour. Normally after flying, the group would get together and find out how the day went. Today was different. One of the senior officers came in and announced, ‘ALL STUDENTS FLY NOW.’ No one had any idea what this was about, but we all got in our planes and flew solo for the next half hour. We found out later it was because one of our student pilots was killed in a plane crash. The instructors forced us to fly, so that we wouldn’t hear about it first and then question our self-confidence and ability. We’d know that we still knew how to fly.” Robert said that each time a crash happened, a few guys from the course would pack up their bags and head home. However, he had no other way to pay for education, so he continued on. “[During training] there was a strange coincidence of the men that crashed. They shared surnames! For example, if there were two Thompson’s, one was killed. If there were two Smith’s, one was killed the next summer. It was strange. I was certainly glad there were no other Heckadon’s in training!”

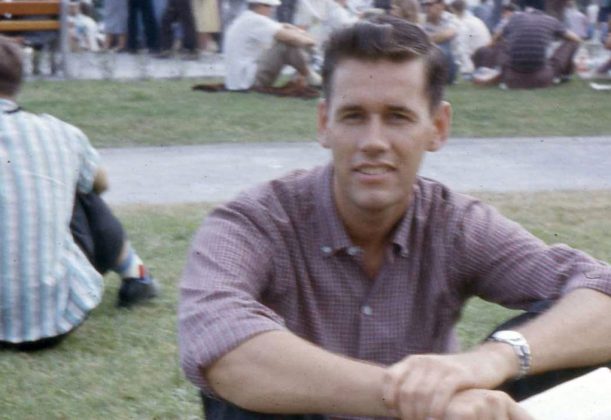

While in the Air Force serving as a First Lieutenant, Robert met his future wife, Camilla. He joked, “I’ve been told that girls like men in uniform.” It was a time in his youth that ended up creating a foundation of confidence and practical skills for his future. It also sparked a creative journey that was just as unexpected.

In 2017, Robert submitted a photography piece to hang in the first Steel Spirit gallery, which showcased artwork and photography from military and service personnel. He had never been a professional photographer, but always enjoyed photography as a hobby. His photo submission was taken in the 1950s from the back seat of a T-33 fighter jet as his fellow pilots flew in formation.

Robert loved taking pictures of his time in the Air Force, though film was expensive, so this resulted in only a handful of good photos and many that were out of focus. After university he was later able to take up crop dusting which helped to pay for his way through medical school. His favourite film was The Best Years of Our Lives, which was about wounded soldiers from WWII. It showed how people coped with lost limbs and reconstructive surgery. Robert went on to specialize in plastic surgery to help people who had been seriously injured.

He went on to become the Chairman of Emergency and Disaster Planning in Essex County, Director of the Maxillofacial Speech Clinic, Chief of Medical Staff at Hotel Dieu Hospital in Windsor and in 2016 was awarded the Chairman’s Medal from the University of Toronto in recognition of being one of Canada’s pioneers in plastic surgery.

Robert’s love of photography evolved over the years into a documentary style. His photos centered on the people, experiences, and things that he truly loved over the years.

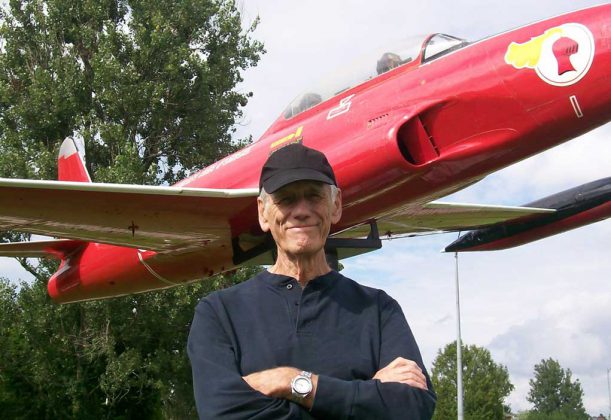

At the age of 84, Robert was thrilled to learn he would be able to hang the photos of his flight training in the gallery, sharing a snapshot of a time that not only marked the beginning of his photo documentary, but that also built the strong foundation for the direction of the rest of his life. Since his time with the RCAF, he always looked at each experience in life as a chapter in a much larger ‘life’ book.

Sadly, just three months before the gallery opened, Robert Heckadon passed away. His biography was framed below the T-33 photos displayed in The Steel Spirit gallery.

Robert’s daughter and founder of The Steel Spirit, Barbara Brown (nee Heckadon), started the first gallery in 2017 to keep busy while her husband was overseas for a year as a war crimes Investigator. With her husband having served on both military and police international missions and her father a veteran RCAF pilot, she wanted to show support for the many other military members and their individual talents outside of the service.

“My husband and father were the inspiration for starting the galleries,” said Barbara. “There are so many layers to individuals behind their jobs. It’s those layers that build each individual story and those stories which inspire others.”

The Steel Spirit has continued to grow and evolve with over 60 artists now involved. Visit www.thesteelspirit.ca to learn more.